“Young people should not need to have the courage to engage in food systems and agriculture. We have to de-risk the investments with financial support mechanisms from the public and the private sector.” said Amanda Wood, Researcher at Stockholm Resilience Center, during the session Promoting Youth in Food Systems – Today and Tomorrow.

Young people should not need to have courage. Barriers to meaningful and sustainable youth engagement in agriculture and food systems need to be understood and addressed. These are the aims of the HLPE report titled Promoting Youth Engagement and Employment in Agriculture and Food Systems. It assesses youths’ engagement in food systems, identifies constraints and challenges, and proposes a global youth agenda. The report was discussed during the Committee on World Food Security’s (CFS) 49th Plenary Session (CFS49), which took place virtually between the 11th and 14th of October 2021.

SIANI has previously engaged with the report by providing feedback based on the discussion at the session Promoting Youth in Food Systems – Today and Tomorrow. This article aims to give an overview of the preliminary framework used in the report, and how the report was discussed during CFS49.

A framework for promoting youth in food systems

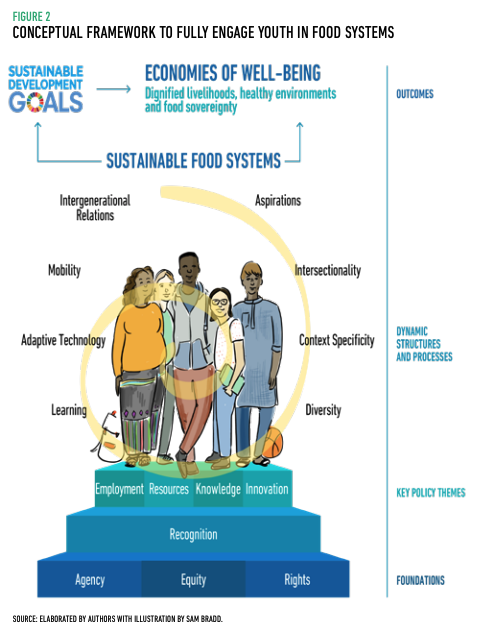

The HLPE develops and presents a preliminary framework on youth engagement in food systems. It informs the analysis of youths’ current engagement and the challenges they face across the four cross-cutting key policy areas: employment, resources, innovation, and knowledge. It also informs HLPE’s policy recommendations. The HLPE identifies four pillars that form the basis of the framework. These are agency, equity, rights, and recognition. According to the HLPE, the transformation to sustainable food systems and the fulfilment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) depend upon these four pillars. So does the transition to economies of wellbeing defined by HLPE as:

“…economic activities, relationships and structures which promote a return to harmonious relationships between people and nature; a fair distribution of resources to address economic inequalities; and healthy and resilient individuals and communities.”

How are the four foundational pillars understood within the framework?

Agency recognises youth as agents of change, but does not prescribe the kind of change youth can catalyse. Instead, the concept neutrally highlights the ability of youth to have some control over the direction of their own life and society at large. However, given that youth are situated in intersecting power relations that constrain their ability to act, the agency of youth is understood to be bounded by context-specific barriers.

Equity reflects that youth are growing up in a world with persisting and increasing inequalities. The inequalities youth face are not limited to their socially defined status as “youths”, but often depend on intersecting factors, such as class, gender, and race. The inclusion of equity entails a recognition of the necessity to address these inequalities for food systems to become sustainable, for the SDGs to be achieved and for the transition to economies of well-being.

Rights incorporate the general “triangle of rights” – protection, non-discrimination, and participation – as applied in various UN conventions, declarations, and specific rights, such as the right to adequate food. The rights pillar entails a recognition of youths as right-holders with a legitimate claim to all the rights enshrined in various international conventions and declarations, including – in the case of children under 18 – the rights listed in the UN Conventions on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). It further entails a recognition of the duty of the State to respond to the right-claims of youths.

Recognition is necessary for the other pillars to have practical meaning for youths. It means that youths are considered full partners in social interactions and able to participate on par with others through the exercise of agency, the pursuit of equity and the realisation of rights.