Cocoa farming was introduced in the Mount Fako region of Cameroon in 1886 by the Germans with the aim of supplying their local factories with raw materials (cocoa beans). They owned and managed vast hectares of cocoa plantations which were worked forcefully by indigenous slaves. After the spread of the crop across the Southern part of the national territory, and the takeover of management by the French and British, cocoa farms were increasingly owned and managed by the peasants but were still maintained for export purposes. Since its independence in the 1960s up until recent years, cocoa production in Cameroon has been championed by smallholders on between 1 and 3 hectares of land.

In 2000, a survey revealed that their farms were underproductive because of ageing cocoa trees (40 years on average). The economic lifespan of cocoa trees varies from 25 to 40 years, depending on the variety. At the age of 40 the tree productivity is low compared to 10 years of age (cocoa productivity follows a bell shape distribution function). A transplanted tree requires 4 years to produce fruit. It is different from variety to variety, but on average, the first harvest is almost negligible, although grows exponentially until about 10 years of age, then begins to decline at about 20 years of age.

Other reasons of lower productivity are high prevalence of diseases like mirids and brown pod rot (fungal attacks on cocoa pods that could account for up to 50% loss in production), and the low use of pesticides and fertilizers due to limited access to credit. However, it is doubtful that the use of fertilizers at this stage can improve the situation. Fertilizers are rather used to raise soil fertility, which may not affect the plant’s physiology.

Among the social factors that led to the under productivity was the physical old age of the cocoa farmers as a result of rural-urban exodus of youths and the lack of attention and maintenance of the farms due to extended periods of low market prices for cocoa beans.

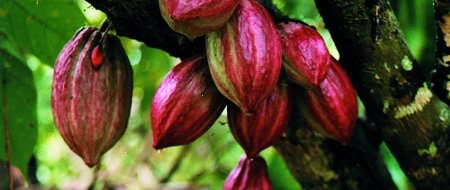

Photo 1: Cocoa pods growing on trees. Photo courtesy of www.icco.org

Photo 1: Cocoa pods growing on trees. Photo courtesy of www.icco.org

The policy-maker’s position in 2000:

As cocoa prices began to rise in early 2000, the government saw a need to raise cocoa production by improving productivity in order to boost exports and foreign exchange. In 2006 it embarked on a “modernization” programme consisting of; 1) sensitizing the farmers on the necessity to reinvest their money and time in cocoa farming; 2) funding research to produce cocoa breeds that are more resistant to pests; 3) multiplying these improved breeds and distributing them at subsidized prices to the farmers and; 4) organizing farmers into cooperatives. Alongside these strategies were efforts to attract younger and wealthier citizens (to fill the gap of the ageing generation and limited access to credit) to cocoa farming by facilitating their access to land, credit, other inputs like fertilizers, pesticides, technical assistance and training.

Photo 2:Sodecao’s nursery of improved cocoa breeds to be distributed to farmers. Photo courtesy of Chi B. Fule

Photo 2:Sodecao’s nursery of improved cocoa breeds to be distributed to farmers. Photo courtesy of Chi B. Fule

The Scientists’ Position in 2013:

A few years after the effective start of the “modernization” programme, concerns began to arise from environmentalists that the rapid deforestation and conversion of forest into farmland may worsen the situation of climate change in the region. They also argued that the massive use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers are detrimental to the natural ecosystem. Some critical observers fear that a changing geopolitical environment in the rural areas through the “modernization” might weaken the stability and democracy of the country, whereby the active presence of elites and politicians (usually large-scale farmers) in the rural milieu serves as a buffer to opposition to the regime in power. Others also expressed the concern that the strategy used by elites is usually to acquire large concessions of land at a cheap rate and re-sell in the future, or resort to a contract farming system whereby they are the landlords while the small farmers exploit the land and they both share the harvest.

These critics incited me to embark on a scientific study aimed at identifying the economic rationale that justifies large-scale farming in the cocoa sector (if any exists). The field research was carried out in March 2013. With the help of a structured questionnaire, I obtained information about the socio-economic characteristics, information about the production and marketing of the produce of forty cocoa farmers in the Nyong and Mfoumou division of the Centre Region of Cameroon. After analyzing my data under the supervision of Sebastian Hess (researcher at the economics department of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences), I had a few interesting results which may be biased due to the size and constitution of my sample.

Photo 3: Some beneficiaries of the project D’Appui À L’Insertion Des Jeunes En Agriculture (Paija) on their farm. Photo courtesy of Chi B. Fule

Photo 3: Some beneficiaries of the project D’Appui À L’Insertion Des Jeunes En Agriculture (Paija) on their farm. Photo courtesy of Chi B. Fule

What my findings reveal:

The large-scale farms were 5-20 hectares in size and their owners were relatively older in age, had more experience in cocoa farming (21 years on average), slightly more educated and had larger households (11 members on average). Despite their large households they spent more on the acquisition of hired labour but at the same time enjoyed economies of scale from the purchase of land, planting materials and pesticides. At the marketing level, they possessed more entrepreneurial skills by managing the farmer organizations, coordinating group selling, negotiating prices with buyers on behalf of their members, offering material credit to members in form of farm equipment like atomizers and pesticides, and providing technical assistance too. “In the future, I plan to convey my harvest (and even buy my neighbours’ produce) to the seaport myself because I think the middlemen make a great deal out of this; we are just labour for them” – these were the words of one of the large-scale farmers.

It was observed that the small-scale farmers were relatively younger in age, had smaller households (five members on average) and fewer years of experience (10 years on average) as well as low level of education compared to the larger farmers. They were less involved in the cooperatives’ activities and had lower selling prices since their cocoa quality was lower and also because they had a lower bargaining power. Yet they have a higher profit margin thanks to the fact that they do not rely on hired but rather family labour (this is in accordance to the African myth that children are a source of wealth for family heads) and community labour; and equally because very few of them buy land since it is most of it inherited. “I do not know exactly when these trees were planted because my father inherited the cocoa farm from his father” acknowledged one of the farmers.

Conclusion

Although large-scale cocoa farmers may attract high selling prices that will cause a spillover effect to the advantage of smallholders, it stands out that they are less profitable. Since their presence given their attributes is vital for the subsistence and growth of smallholders, strategies aimed at encouraging their co-existence and interaction in a mutually beneficial way seems to be a plausible way forward. An active farmer organization or cooperative that can adapt to the needs of its members, managed by members with better managerial skills and governed transparently provide fertile grounds for the development of its members and strong rural institutions that can partake in policy designing.

Based on my findings, small farmers are not as motivated as the large farmers when it comes to engaging in group activities although they are able to obtain some benefits like credits in form of pesticides before harvest. Farmers who receive such benefits are obliged to sell their produce via the cooperative so that the debt can be refunded. Meanwhile farmers without such benefit may also be seeking high selling prices for their produce and may also be compelled to improve on the quality of their produce before it is channeled through the cooperative.

I also observed that in localities where dynamic cooperatives were absent, large farmers were not present equally. Finally, small farmers are more commonly the beneficiaries in farmer organizations; therefore it would be hard for the market schedules to take their limitless needs into account – leading to their discouragement.

In my opinion, cocoa farming in the Nyong and Mfoumou division presents a huge potential for organic cocoa, as chemical fertilizers have not yet been used in the region. However, it is evident that fertilizer use is inevitable in the long run since it is a method of replenishing or replacing the nutrients absorbed by the plants. In my opinion, the use of fertilizers in Cameroon has always been that of setting up institutions that ensure application of fertilizers in an environmentally acceptable way, following strict prescriptions from soil scientists.

Additionally, potential for the organic cocoa production can also be realized through cocoa certification (fairtrade) so that the farmers can benefit from a premium as well as through the possibility of transforming cocoa beans at least into grindings and cocoa butter before exporting it out of the region. Since all these entail huge financial costs that would yield profit only in the long run, the government can facilitate farmers with access to credits and technical support. In is worthy to note that, faced with the challenges of climate change, it is important to maintain cocoa farms at a small scale of say 5 hectares maximum that would enable the famers to monitor their farms effectively without running the risk of incurring extra costs accruing from moral hazard.

About the author:

Chi B. Fule is a master student in the European Master in Agricultural, Food and Environmental Policy Analysis (AFEPA), an Erasmus Mundus programme. She is also a supporting staff at the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MINADER) in Cameroon. She holds an engineering diploma in agricultural economics and rural sociology from the University of Dschang, Cameroon.

References:

Document de Stratégie de Développement du Secteur Rural (DSDR), 2005.

Elong, J. G., 2011. L’elite urbaine dans le projet de la relance de la cacaoculture par la SODECAO dans le Cameroun forestier in L’elite Urbain dans l’Espace Agricole Africaine. L’Harmattan