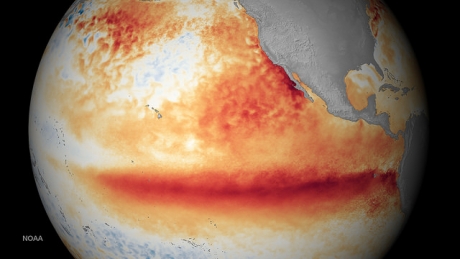

El Niño marched the headlines throughout the last year. The El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, is a reoccurring weather phenomenon resulting in higher sea surface temperatures and air pressure over the Pacific.

What makes El Niño a complicated issue is that its’ effects and consequences differ from place to place. Generally, the effects include long periods of drought and erratic rainfall patterns. However, sometimes both of the two can occur within the same country at the same time, but in different regions. This blogpost gathers information about common problems associated with El Niño, building on the examples and impact stories from around the world. It also synthesizes information from reports, scientific articles and interviews with meteorologists and representatives of civil society.

Agriculture & Livelihoods

Many of the world’s rural poor depend on rainfed agriculture or pastoralism for their livelihoods. Countries affected by the latest 2015-16 El Niño, like Ethiopia, experienced long periods of drought in the years before this El Niño. When harvest decreases, farmers face a double challenge: they try to compensate for low productivity through more intensive land use, and they do so farming fatigued soil, which is already strained and hardened, with reduced ability to filter fluids. Hard soil also increases the risk of flash floods – an outstanding example of this event happened in Malawi where houses and farmlands were washed away, displacing hundreds of thousands of people.

When livestock die and harvests fail, many farmers are forced to sell their agricultural assets and abandon their current livelihoods. This also impacts hired farm laborers because demand for their services falls. In countries like the Philippines, forest fires linked to drought burnt down 2 million hectares of forest that provide livelihoods for many people. Warmer weather also increases the strength of storms. In Fiji a cyclone completely destroyed harvests in the hardest hit areas. El Niño events also increase the pressure of domestic migration because many rural dwellers move to cities.

Due to the fact that entire regions can be affected simultaneously, the ability to import food decreases as neighboring countries can be struggling with food deficits as well. Trade barriers and additional costs related to food imports from further away add to ecological and economic stress of the affected countries.

Food prices also increase due to food shortages. For instance, food prices in the Democratic Republic of Congo increased up to 50 percent, hitting farming households especially hard because their incomes had already gone down due to harvest failure.

Health and education

When wells dry out and access to water diminishes, people have to turn to less hygienic and often stale water sources which are more likely to carry diseases like malaria, cholera and other gastro-intestinal infections. In addition, food shortage reduces resistance to diseases, especially in countries with high child malnutrition. Chronic hunger affects people’s ability to concentrate, which leads to lower work output for adults and makes it hard for children to focus in school. Higher food prices make it hard to afford school fees, and when the economic situation at home calls for more water fetching or help with other house duties, many families decide to take their children out of schools.

Satellite image of the 2015 El Niño in November 2015. Photo credit: NOAA ESRL via Flikr (CC BY 2.0).

Satellite image of the 2015 El Niño in November 2015. Photo credit: NOAA ESRL via Flikr (CC BY 2.0). Former United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon pose for a group photo to help promote the Sustainable Development Goals. Photo credits: IAEA Imagebank via (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Former United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon pose for a group photo to help promote the Sustainable Development Goals. Photo credits: IAEA Imagebank via (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).