Rodent damage to pre-harvest yields

Food losses due to rodents are staggering. In Asia alone, annual food losses due to rodents would be enough to feed 200 million people each year. Rice pre-harvest losses are estimated to be between 5-10% in most Asian countries, however in some countries it is expected to be significantly higher, such as Indonesia where yield loss estimates are around 19% which is the equivalent of enough grain to feed 39 million more Indonesians. However, the destruction caused by rodents on a localized level can be devastating where rodent outbreaks can wipe out entire harvests and lead to famine like conditions.

The large grey areas of damaged cropland in the picture were caused by rodents.

The large grey areas of damaged cropland in the picture were caused by rodents.

Causes of rodent outbreaks

While there are different causes of rodent outbreaks, all lead to a situation whereby there are higher than normal amounts of available food which rodents have access to. Rodent outbreaks have been categorized as being cyclical or evolutional, climatic, or anthropogenic.

Rodent outbreaks which occur due to natural cycles include the masting or flowering of plants such as bamboo. In 2007, many poor rural communities in India, Myanmar, Bangladesh and Laos PDR were affected by such events and required food aid.

Unusual climatic events such as heavy rainfall early in the wet season or flashfloods and cyclones can cause rodent outbreaks. Heavy rainfall before the beginning of the crop season, for instance, can allow the rodents’ breeding season to begin earlier due to better than usual food supply therefore the breeding season is extended which increases rodent numbers in the rice fields.

The third cause of rodent outbreaks is due to the management of cropping systems whereby there is an anthropogenic response to an extreme climatic event or market forces. The expansion of cropping areas and the intensification of cropping systems increasing the number of crop seasons per year are seen as major inducers of anthropogenic rodent outbreaks.

Problems with typical rodent control methods

Throughout South and Southeast Asia studies have shown that rice farmers perceive rodents to be their number one pest or the pest which causes the most damage to their yield. Farmers set traps up themselves or use professional rat catchers, however perhaps the most common technique is the use of rodenticides. This is despite the fact that farmers are concerned that rodenticides may have adverse effects on their own health. There are also concerns, albeit not from most farmers, that rodenticides threaten non-target rodent species which are not pests and in fact provide important ecosystem services to the area.

Farmers also tend to wait until they notice damage caused by rodents which is usually in the later stages of the rice cycle, and which is often too late to avoid yield losses. Researchers argue that failing to control rodents early on in the season leads to an explosion of rodent numbers later on at the time of harvest.

Rodent control practices are usually undertaken individually by farmers rather than collectively. This practice has been criticized by researchers who argue that collective action is needed. This is because the rodents’ habitats can span many farms as the typical size of rice farms in Asia is no more than 2 hectares while rodents can have a home range of 10-15 hectares.

Rattus Argentiventer, more commonly known as the rice field rat is the major rodent pest in much of Southeast Asia

Rattus Argentiventer, more commonly known as the rice field rat is the major rodent pest in much of Southeast Asia

Ecologically-based rodent management systems

Much of the research which aims to tackle rodent outbreaks focuses on reducing yield damage in a way which does not harm non-targeted rodent species and is referred to as ecologically-based rodent management (EBRM). There tends to be a mixture of methods used in EBRM which includes arranging collective rat hunting campaigns in the early stages of the crop cycle, getting neighboring farmers to synchronize their crop seasons and constructing trap-barrier systems (TBS).

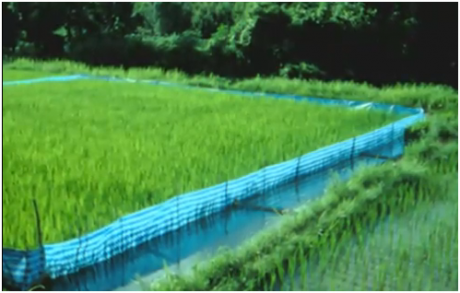

TBS is a fenced off area within the rice field where an early crop is planted several weeks before the main crop. The entrances to the TBS contain traps so the rodents are trapped as they try to get to the early crop inside. Studies have shown EBRM as being effective in reducing rodent damage as well as reducing farmers’ use of rodenticides. TBS alone has been shown to increase rice yields 10-25%.

Despite the positive findings of EBRM, its practice by rice farmers is still low which is believed to be because of, among other things, cultural constraints such as an absence of cooperation amongst farmers. A lack of understanding of rodents’ ecology is seen as another constraint to EBRM application as well as the fact that many rice farmers are living close to the poverty line and are unwilling or unable to invest in new rodent control practices.

The picture shows a trap-barrier system (TBS). An early crop has been planted within the TBS to attract rodents who can pick up the smell of the crop. The rodents are then caught in traps as they go through the entrance of the TBS.

The picture shows a trap-barrier system (TBS). An early crop has been planted within the TBS to attract rodents who can pick up the smell of the crop. The rodents are then caught in traps as they go through the entrance of the TBS.

Risk of more frequent rodent outbreaks in the future

Cyclical outbreaks are even more destructive to many poor farmers’ livelihoods than first believed as it is now acknowledged that these events such as the flowering of bamboo do not happen simultaneously but can instead take 2-3 years to complete. This only prolongs the availability of food and therefore lengthens the breeding season of the rodents.

Climate change and extreme climatic events, such as an increased variation in mean precipitation are expected to change the length of breeding seasons and therefore the ecology of rodents is likely to become more unpredictable given its adaptability which suggests rodents may become even harder to control.

Perhaps the greatest impact will come from anthropogenic responses to climatic conditions and market forces. A common worry by researchers has been the intensification of many countries expanding agricultural areas and increasing the number of crop seasons per year which reduces fallow periods and therefore extends the supply of food for rodents which prolongs their breeding season. Ironically, food security puts pressure on countries to intensify cropping systems; however these steps are only likely to increase the severity of rodent outbreaks to food losses.

Biography

Adam John is a PhD economics candidate at the Agricultural and Food Policy Studies Institute at Universiti Putra Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and is based in Stockholm. He is has a Master’s degree in Economic Development from Reading University and is expected to defend his thesis at the end of 2013 which is entitled ‘World rice price volatility. Consequences and causes’.

The pictures were taken by Dr Grant Singleton from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) who is one of the leading experts on ecologically based rodent management.