The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by all United Nations Member states in 2015, took a stand compared to the previous goals, not just aiming for increased sanitation coverage but for 2030 to ‘ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all’ (SDG 6). Sanitation is vital for health and dignity, particularly for menstruating girls’ school attendance. Toilets provide sanitary conditions for the user, whereas the safe management of excreta aims to prevent ”downstream” contamination and disease transmission. Despite progress, 3.5 billion (43% of the global population) lacks safely managed sanitation services. A role of sanitation stressed in SDG 6, but often neglected, is providing nutrients to agriculture. Since the nutrients in the consumed food end up in the excreta in a constant flow, sustainable nutrient management of food production needs to consider this untapped resource.

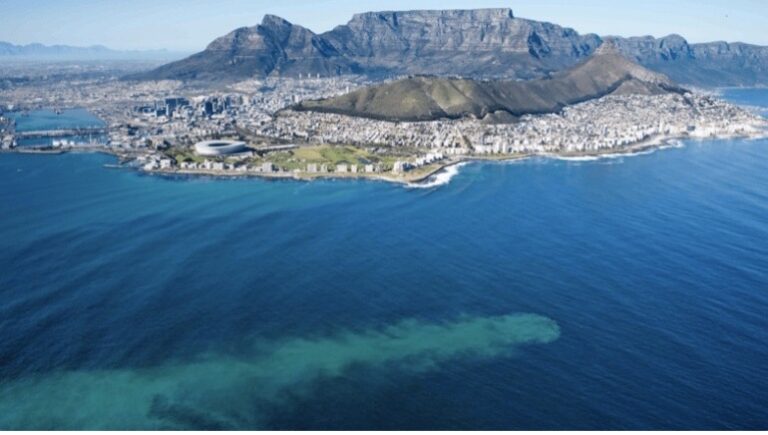

In South Africa, a large proportion of the population (81%) uses improved (i.e. for the user judged safe) sanitation facilities. 57% of these are solutions based on flushing and connected to a sewer system, whereas 34% have on-site sanitation solutions such as ventilated pit latrines and traditional, non-ventilated pit latrines. Being a water-scarce country, the South African 2016 National Sanitation policy emphasizes the importance of responsible use of water resources both in terms of water use and protection of the water environment. For this reason, on-site sanitation is recognised as an acceptable long-term and decent sanitation service that may help fill the sanitation gap for the more than 5 million South Africans who do not have safe sanitation solutions.

Faecal sludge management in South Africa

” The provision of sanitation services has to be responsive and adaptive taking into cognisance that South Africa is a water scarce country coupled with prolonged droughts in recent years…” Senzo Mchunu, Minister of Water and Sanitation (FSM strategy 2023)

Increasing the sanitation coverage with on-site solutions is, however, challenged by on-site management and faecal sludge management services being limited and severely challenged, and poor servicing of on-site sanitation options has led to facilities perceived as unhygienic. In contrast to water-born sanitation systems, the on-site sanitation management chain has many broken links with unclear responsabilities and mandates. To overcome these challenges, a National Fecal sludge management (FSM) strategy was released in 2023. The 10-year FSM strategy for South Africa aims for clear regulatory and financing frameworks across the service chain; the development of a variety of appropriate and affordable on-site sanitation technologies; increased capacity along the service chain and the ingration of private sector service providers.

Fertiliser potential in excreta and soil health

Agriculture in South Africa is challenged by water scarcity, drought, land degradation and soil erosion. To maintain agricultural yield, it is vital to replace nutrients removed with the harvest so that the soil is not mined on its nutrients. However, soil degradation is a vicious problem since the response to plant nutrients is limited for degraded soils, especially with mineral fertilisers supplying most often only a few macronutrients and no organic matter. Compounds that conventional waterborne sanitation sees as problems/pollutants (i.e. the nutrients and organic material) can serve as valuable input to agriculture, and the 2016 South African National Sanitation Policy encourages the reuse of the products of sanitation services. Apart from containing all the nutrients we have consumed, from macronutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium to trace elements, the excreta also contains recalcitrant organic carbon that can improve water holding capacity and and provide soil nutrient supply over several seasons. Nitrogen has been estimated as the main constraint for South African smallholder maize production. By applying human urine at a rate of 4 kg N/ha, in addition to ordinary practice, maize yield could increase with an average of 12 % across South Africa (Andersson et al. 2013).