Climate change, volatile prices, changing consumption patterns, and increasing competition for agricultural land makes the hard business of farming even more challenging. How do we make our farming systems sustainable and resilient?

In search for the answer to this question, we tend to focus on inputs and outputs, forgetting about the people who are at the center of the issue. However, perhaps it is the understanding of farmer behaviour that can fill in the gaps in our search for sustainable farming solutions that will work on the ground.

What do farmers think when they make decisions about managing their farms? And how do changing conditions influence these decisions? These are the questions we explored in the paper “Researching farmer behavior in climate change adaptation and sustainable agriculture: Lessons learned from five case studies” recently published in the Journal of Rural Studies. Building on five case studies, we developed a framework for studying farmer decision-making and adaptation to change. The cases we looked at included potato farming in the Colombian Andes, slash-and-burn agriculture in the Philippines, winegrowing in California’s Napa Valley, peri-urban maize production in central Mexico, and smallholder cotton farming in India.

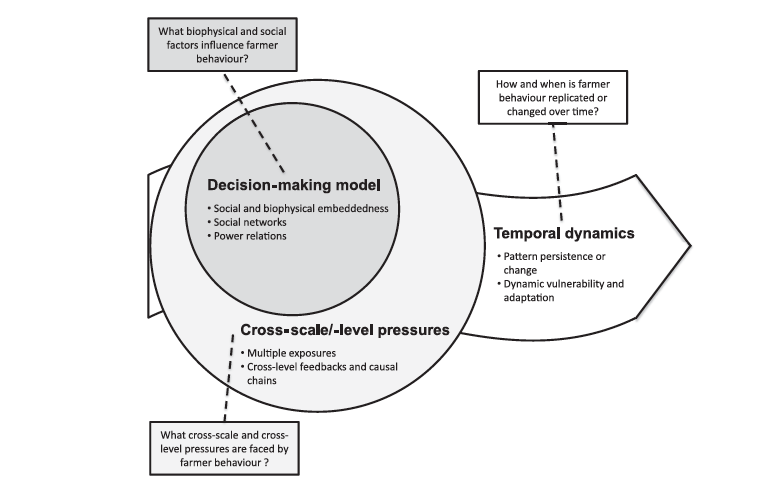

The framework helped us to find three critical areas of knowledge we need to explore in order to understand farmer decision-making processes:

1) understanding how farmers respond to environmental and social context;

2) the interaction of many different influences from across scales at the same time;

3) and how farmers act over time.

Framework for studying farmer decision-making and adaptation to change.

Framework for studying farmer decision-making and adaptation to change.

First, we found that farmers make individual decisions in response to both their biophysical environment and to their sociocultural context. A wine-grape grower in California irrigates based on the weather, a potato farmer in Colombia sprays pesticides in response to infestations – these are examples of responses to the biophysical environment.

Farmer response to social and cultural factors includes, for example, the maize-growing tradition in Mexico based on knowledge from many generations. The farmers identify themselves as maize farmers, they enjoy the taste of their homegrown tortillas, and they see growing maize as “what the land does”. Hence the communities continue to cultivate maize for subsistence even in the face of increasingingly market oriented agriculture and booming demand for land from urbanization.