Anyone who has been to a Southeast Asian capital remembers the constant background noise of honking vehicles and the exhaust gas brume, drills and metal clinking, karaoke and chatting people. One day, Hanoi exchanged all those sounds for bird chirping, more bird chirping and an occasional police truck with loudspeakers telling everyone to go home.

January: I’ve been in Vietnam for the last 10 years as a climate change scientist at the World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF), and was just about to visit a project site in Myanmar, when the coronavirus reached Hanoi. My friend and I are watching the press conferences with the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), praising the Government of China in responding to the virus, outlining that the epidemic is not yet a pandemic. The wording of his praise alerts our disaster antennae. “What is he waiting for?” we ask ourselves. Then Wuhan locks down.

Part 1: Realisation

Wuhan in China, and Hanoi in Vietnam, 10 million people in each city and the same distance in between as Milan in Italy (the epicenter of the European virus) and Gothenburg, my birthplace in Sweden.

Lunar New Year is approaching, which means millions of holiday travelers in China and Vietnam.

“Perfect growing grounds for viruses,” says the rational me.

February: Vietnam stops flights from China. This New Year will be different, many Vietnamese go to the countryside and stay there. The pavements, usually serving as motorbike parking, are now walkable and filled with watermelons dumped from 1.5 to 0.5 dollars per kilo. They hadn’t made it to China before the borders closed. The air quality index falls from red to orange.

March: Suddenly the virus hits Europe.

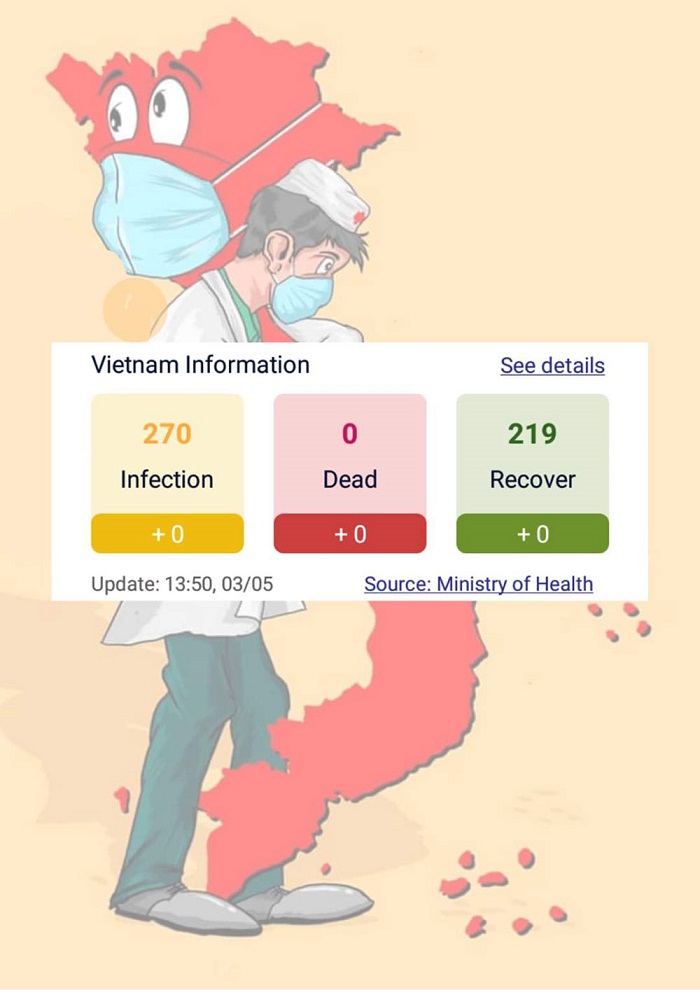

Within one week, Italy is in chaos. Hanoi still has zero dead and few infected. We follow the news to try to understand: How come so many are dying in Italy and France? How come so many Koreans contract it? And how come Vietnam is so spared?

One morning, the buttons in the office elevator are covered in plastic tape and it smells of overnight disinfectants. Our ‘last’ meeting for the new project consists of ten people around a conference table, all wearing face masks.

“Vietnam learned from SARS,” says my local shop owner, while spraying the money with disinfection. “We managed that, we can manage this too.”