This is an interview piece with Andrea Caputo Svensson, Global Health Advisor at ReAct – Action on Antibiotic Resistance

As people become more aware of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), how does AMR play a role in aquaculture?

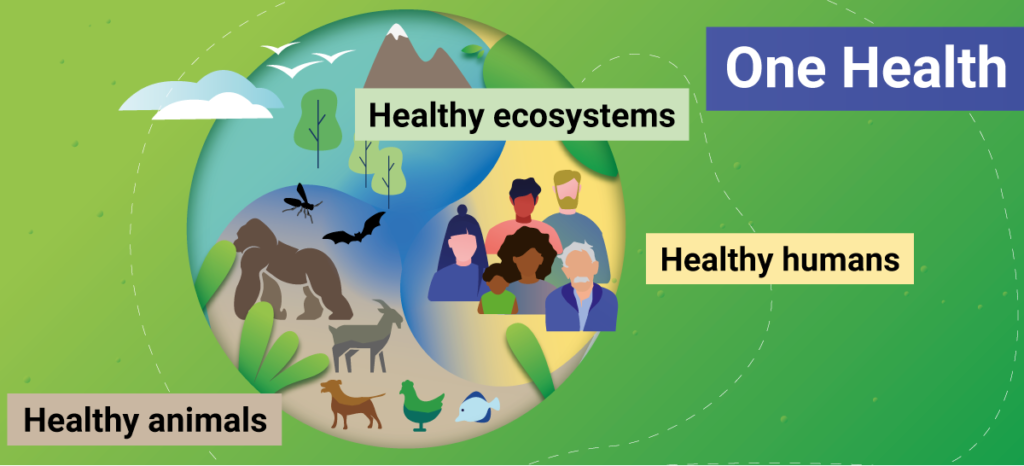

The increasing awareness about antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in agriculture can be attributable to the rising political dialogues on food safety and security. What is unique about agriculture, including aquaculture, is that it can be seen as an interactive platform between food security, the environment, and human health. Hence a clear example of the One Health concept. More so, how the use of antibiotics in farming animals can have an impact on the environment as well as on human health.

Furthermore, aquaculture is vital in comparing the use of antibiotics in any of these areas. Water as an element is also essential because water, one of the primary vectors in the spread of AMR, connects the environment to animals and humans when contacting with contaminated water.

How is the health of humans and aquatic animal products interlinked?

We have seen some cases in India and other parts of the world where the hospital wastewater ends up in aquatic systems of fish and shrimp farms. This water, which may already contain resistant bacteria or even residual antibiotics, arrives in shrimp hatcheries that already use antibiotics to control or prevent various diseases. And then the same water, at the same time, is also used for irrigation purposes. In extreme cases, this wastewater could even be used for drinking or domestic purpose.

Water quality is paramount, as pathogens can be transmitted through human, animal and the environment, whose health is intrinsically intertwined and interdependent. This makes human exposure control and hygiene important features of aquaculture programmes. As we have seen with COVID-19, AMR is a global concern that impacts all countries and people. Similarly, AMR respects no borders and can quickly spread through movements of people, animals, food or water. Hence, human health is strongly linked to ecosystem health.

What is the use of antibiotics in aquaculture?

There must be a specific purpose and diagnosis for the farmer to use antibiotics. In Europe and North America, antibiotics are regulated under veterinary prescription, and antibiotics for growth promotion are forbidden. However, this is not the case in other countries, specifically in low- and middle-income countries where the use of antibiotics in farming animals is not regulated, or not implemented even when a policy framework exists.

In the absence of such frameworks, antibiotics are overused both as an infection-preventive measure, for example as part of the so-called ‘medicated feed’; and/or to treat diseases, independently of their nature (bacterial or viral) without consulting a veterinary expert. In either practice, huge quantities of antibiotics are massively poured into entire water tanks, exponentially accelerating the accumulation of antibiotic residues, hence the potential development and spreading of AMR.

So what needs to be changed in AMR in aquaculture to ensure One Health?

This is a million-dollar question. Honestly, no silver bullet will save and solve everything, but creating or implementing country-specific policy frameworks and good practices, coupled with systematic monitoring and surveillance, can help contain AMR.

Norway is an excellent example, as they have reached almost zero use of antibiotics in salmon farming. Also, Chile has managed to lower antibiotic use to certain levels. So, one of the main actions to reduce the use of antibiotics is through preventative measures, such as vaccines. But there are other methods. Less-known alternatives include bacteriophages, quorum quenching, probiotics, prebiotics, and antibodies (Bondad-Reantaso et al., 2023, in print). However, the first and foremost action is connecting experts from different disciplines, organisations, and the authorities concerned.

I want to mention my recent publication as a consultant for FAO, where we looked at the implementation level of the AMR National Action Plans (NAPs) specifically from an aquaculture perspective. As most countries have finalised their mandates, we analysed 95 NAPs based on a “One Health” approach for AMR, including whether funding for NAP implementation was allocated, and whether the decision-making authorities were involved.

In the analysis, almost 40% of the countries, even some of those ranked among the top 15 aquaculture producers worldwide, did not mention any aquaculture components within their AMR NAP. The study highlighted the gaps in AMR-aquaculture governance, meaning that the policy framework will only be functional in addressing the AMR issue if it is sustainably planned. This includes the allocation of long-term funding for well-detailed activities, accountability of the responsible authorities, establishment of indicators of implementation, and consistent monitoring of implementation levels, among other parameters.

Aquaculture is controversial. It reduces fishing pressure, serves as a potential solution to food insecurity, and offers nutritious food locally in low- and middle-income countries. But at the same time, aquaculture has negative impacts on the environment. How can we reduce AMR in aquatic food systems?

As previously mentioned, the fact that there is less rigid regulation in some low- and middle-income countries is definitely a big issue. Some changes are going in the right direction. For example, the European Commission increased the screening of India’s shrimp consignments for residues up to 50% from 10% in 2016, as well as recently updated the list of antimicrobials reserved for human use. In this way, Europe is aiming to improve the quality of imported food commodities, while increasing the pressure on low- and middle-income exporting countries to comply with European Union legislation, considering aquaculture represents their main source of livelihood.

However, what happens with the seafood commodities that do not pass the export controls? As we have seen in India, the aquaculture commodities that could not be exported due to AMR-related issues have been redirected to the local market, hence only geographically shifting the issue. Therefore, beyond international trade, there is still a need for more control of antibiotics and AMR-parameters in aquaculture at national level.

Monitoring and surveillance of antimicrobial usage and AMR within the aquaculture sector requires a radical change. We need to reassure farmers that committing to implementing practices in minimising the need for and use of antimicrobials will not affect their productivity. In case of infection, it is vital to mention the role of the experts and of the responsible authority to facilitate controlled solutions for infectious diseases and AMR, and ensure coordination among the different AMR stakeholders — from consumer to producer, including veterinary up to the regulatory authority.

What is the AMR situation in Sweden?

Sweden has been doing good because of its strategic programme against antibiotic resistance since 1995, which has been essential to counteract AMR. Data from the University of Gothenburg showed the Swedish work on the containment of antibiotic resistance and found that the use of antibiotics is lower in aquaculture than in livestock, even though the overall use of antibiotics in food animals is relatively low in Sweden.

There is a good level of awareness and education on AMR, and the population can access accurate information from reliable sources and trained experts.

What could be seen as good practices to address AMR in a One Health approach and foster compliance with antimicrobial use?

Antibiotic resistance has multi-facets and different drivers. The One Health approach requires a multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary strategy considering human, animal, and environmental health, and this is especially important, as we have seen in the integrated aquaculture systems. Some good practices identified are coordinating actions among experts in different sectors, and establishing scientifically-sound AMR indicators.

There are some examples where the need to set up a governance structure has been more evident, e.g. the recent finding shows that more than a tonne of antibiotics was used to control a potentially deadly fish disease at two salmon farms in southern Tasmania in early 2022. To this end, besides the aforementioned policy frameworks, more research needs to be done, for example, to examine the impacts of fish farming on the sediment and water near open aquaculture systems.

It becomes clear that more funding is needed to sustain continuous research in understanding the complexity of AMR, and harness this data to support policymakers in addressing the AMR issue globally.

What more can individuals, civil society organisations, research centres and policymakers do to continue educating about this global health threat?

Education is a keyword. For example, at ReAct, we provide training materials to improve awareness and understanding of the complex nature of antibiotic resistance, among students, practitioners, and policymakers. Consumers, professionals and governments must be adequately informed and guided on the appropriate use and prescription of antibiotics, as well as on the consequences of inaction towards antibiotic resistance for global health. Not least, ReAct provides a Toolbox to guide the process of developing and/or implementing national action plans, as well as inspirational examples to take action on addressing antibiotic resistance.

This interview piece is part of SIANI’s ‘Tune in to Food Systems’ interview series composed of monthly interview articles with experts across fields dedicated to sustainable food systems.