This is an interview piece with Jennifer Clapp, Vice Chair of the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE-FSN) of the UN Committee on World Food Security, and newly elected fellow to the KSLA General section, on inclusive science-supported food policies.

1. What is the role of science and expertise in shaping global food policy nowadays? How can we legitimate the science-policy interface for global food systems?

The need to transform food systems to meet global sustainable development goals while reducing negative contributions to climate change is more urgent than ever. While most agree on the need for food systems transformation, there are very different interpretations of the best pathways to get there.

In this context, communities with food systems expertise must provide balanced, evidence-based inputs to move policy forward in ways that address the major problems facing food systems. However, even this process can be fraught and politicised, and as such, it is important that the delivery of scientific advice to policymakers is widely perceived to be legitimate so that policy advice is accepted and taken on board. Failing this, making policy recommendations that are at best ignored or at worst captured by the interests of a few powerful food system actors.

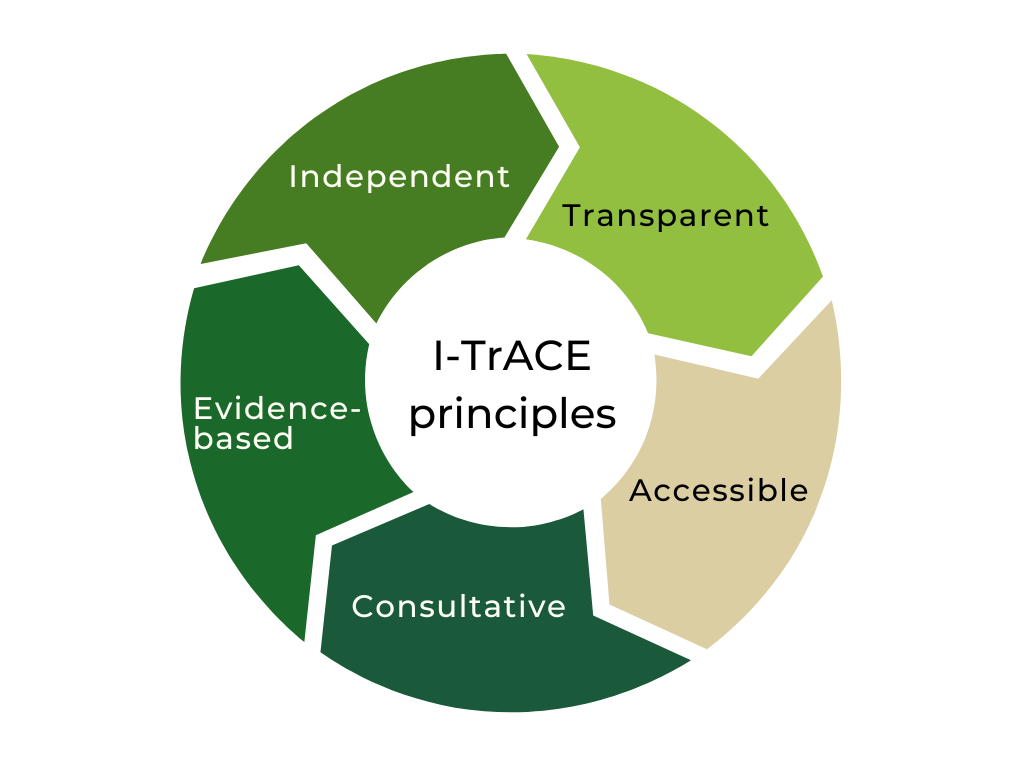

This is why with colleagues from the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE-FSN), we recently mapped out the principles we see as necessary for legitimate scientific contribution to food systems policy advice, which we call the I-TrACE Principles. This stands for:

Independent (processes must be independent to ensure their impartiality and the consideration of evidence from different sources);

Transparent (processes must be open and disclose all sources of information and acknowledge where there are disagreements);

Accessible (data must be open and available and findings must be translated in a way that is understandable for policymakers and the public);

Consultative (evidence gathering processes including traditional and indigenous knowledge, and those who are most marginalised within food systems); and

Evidence-Based (evidence must be collected from a diverse range of sources and perspectives from a number of different fields and knowledge holders).

These principles are meant to guide science – policy – society interfaces for food systems in ways that ensure that both processes of evidence gathering and assessment, as well as the policy recommendations that come out of the process, are widely perceived as legitimate by all food system stakeholders.

2. What are some of the unique considerations for the application of science and expert knowledge in food systems?

Food systems are unique in that they serve multiple and overlapping functions in society. It is therefore important that science and knowledge that is brought forward to inform policymaking is mindful of the potential for different priorities and viewpoints among stakeholders and food system participants. For example, food is a basic human need that provides nourishment for human survival and flourishing, and it is also widely recognised as an international human right. Food systems also provide livelihoods for nearly a third of humanity, although those livelihoods can look very different in rich and poor countries and among different food system actors. Food systems are also deeply enmeshed in ecosystems, and they serve as a cornerstone of cultural norms and practices in societies. Food may be a market commodity, but it is not solely a market commodity.

Given the diversity of participants and viewpoints regarding the main functions of food systems, it is vital that science and knowledge that is brought to bear on food policy take these different viewpoints into account through consultative practices, and to do so through transparent processes. It is also important to consider a wide range of sources of evidence coming from different disciplines and knowledge holders. Taking this information into consideration should be a body that is independent and able to translate findings in an accessible manner. There will likely always remain differences and viewpoints regarding the key functions and roles of food systems given the diversity of actors within those systems, but it is important that we work toward a common understanding and recognition of this diversity, rather than prioritising one approach over the other.

3. What are the main challenges of getting policymakers to adopt science and knowledge-based policy advice? How can those challenges be overcome?

Although knowledge and science-based advice can enhance its legitimacy by following the processes and principles I outlined above, it is not automatic that governments and other actors will necessarily follow that advice. The formulation of international food policies is still dominated by governments, and those governments still have certain interests that they may be seeking to advance. In this sense, they may find some policy recommendations to support their interests, while others do not. This does not mean that the policy advice is wrong; it simply means that different actors may still prioritise their own interests even in the face of evidence-based policy advice.

It is important for policy and decision-makers to take a step back from their interests – be they commercial or geopolitical – and consider evidence-based policy recommendations at their face value. States can also make prior agreements on how to address problems such as emerging food crises before they happen, such that their interests do not hinder the need to take action.

4. Are there good examples of science and knowledge-based global food policies and processes and what were the key factors for success?

There are examples of science and knowledge-based policy advice that is fed into food systems policymaking at the international level. For example, the HLPE-FSN has provided important reports that have informed decision-making processes regarding policy convergence at the UN Committee on World Food Security (CFS). HLPE-FSN reports on food systems and nutrition, agroecology, and land tenure have all fed into such policy convergence processes within the CFS. HLPE-FSN insights on land tenure, for example, have resulted in one of the more successful policy convergence processes, the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Land Tenure (VGGT), which have been widely adopted and just celebrated its 10th anniversary.

5. What about the arguments that reject or downgrade Traditional Knowledge in the name of science-informed and evidence-based food systems policies?

Food systems serve multiple functions in society, and as such many different actors within food systems hold different kinds of knowledge about how those systems work and the key challenges facing those systems, as well as the kinds of measures necessary to address those challenges. In other words, a diversity of actors bring evidence forward that is important to incorporate into policy advice – and that includes Traditional Knowledge holders, such as that from Indigenous Peoples, as well as from marginalised participants in food systems whose lived experiences are vital for policymakers to understand. It is important to recognise the significance of these kinds of Traditional Knowledge as a legitimate input into evidence-based food systems policy advice, and not to only prioritise knowledge coming from Western-trained scientists in academic settings.