”To build a sustainable, climate-resilient future for all, we must invest in our world’s forests. That will take political commitment at the highest levels, smart policies, effective law enforcement, innovative partnerships and funding.” Ban Ki-Moon

Forests are key to climate solutions. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), when cleared, forests contribute to about one sixth of global carbon emissions. On the other hand, standing forests have the potential to remove 10% of all global carbon emissions projected for the first half of this century. Forests are also biodiversity hubs; the Amazon forest, for example, is home to one in ten known species on the planet.

Visit of recently deforested site to grow Naranjilla, a locally used fruit. Photo by Torsten Krause.

It has been ten years since the global climate community agreed that a financial mechanism to support reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) must play a role in fighting climate change. Since then, a vast number of research projects have studied how REDD+ can be implemented in practice, and it has become apparent that paying local landowners for keeping trees is not a fix for sustainable forest management in its own right.

Instead, research and practical experience show that promoting sustainable tropical forest management requires robust and effective financial, governmental, and social institutions to manage forests and money fairly.

How can institutions be strengthened?

Firstly, it is important to acknowledge that every country, and in many countries even every region, has unique institutional setting with context specific traditions, legal frameworks, land ownership structures, and local cropping, hunting, and forestry practices. Most of the world’s tropical forests are located in rural isolated areas, where institutions tend to be weak. There is a general agreement that these institutions need to be strengthened for REDD+ to work in practice. However, how to best strengthen institutions to reduce deforestation is debated. The divide is between government-led (“top down”) institutional measures, which may be perceived as more efficient, and “bottom-up” efforts, which may be perceived as more fair or inclusive. However, what if these two approaches could be combined?

The research team preparing for interviews in the communities. Photo by Kimberly Nicholas.

In our new study published in the journal Ecology & Society, we evaluated the institutions governing Indigenous people’s participation in a national forest conservation program in Ecuador, the Programa Socio Bosque. The program aims to cover 4,000,000 hectares and enroll 1 million people by providing an economic incentive to promote both forest conservation and poverty alleviation, and is a key part of Ecuador’s REDD+ strategy. Indigenous communities occupy more than 20% of the Amazon forest, and have their own formal and informal institutions for managing forest resources sustainably. We conducted fieldwork and interviews in four different indigenous Kichwa communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon that receive financial incentives from Socio Bosque for protecting the forests on their land.

Governing the commons in Kichwa communities

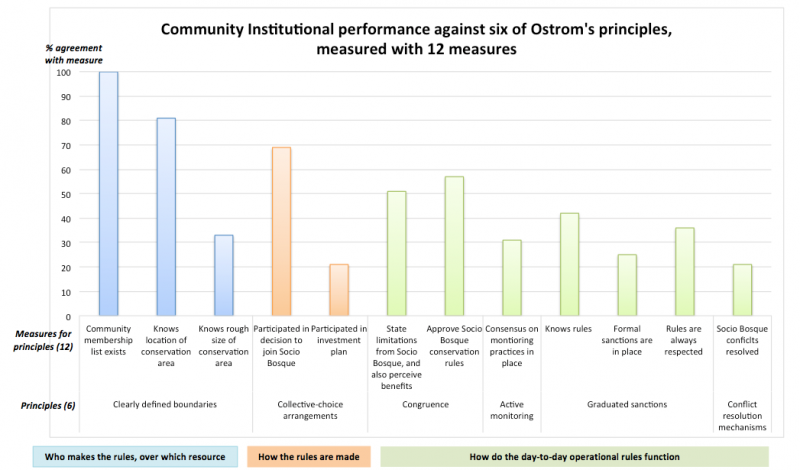

We evaluated local community institutions using six principles derived from the theory of collective action for common pool resource management developed by Nobel Prize winner Elinor Ostrom. This theory has some structuring principles for managing common pool resources: resource boundaries have to be clearly identified, rules that balance between costs and benefits and are aligned with local norms (congruence), those who make the rules are also governed by them (choice), active monitoring, graduated sanctions for noncompliance with the rules, and a mechanism to resolve conflicts. Basing on these principles, we constructed 12 measures of local institutional performance in the four communities studied (Figure 1).

Conducting interviews with community members in the Province of Orellana. Photo by Wain Collen.

Conducting interviews with community members in the Province of Orellana. Photo by Wain Collen.

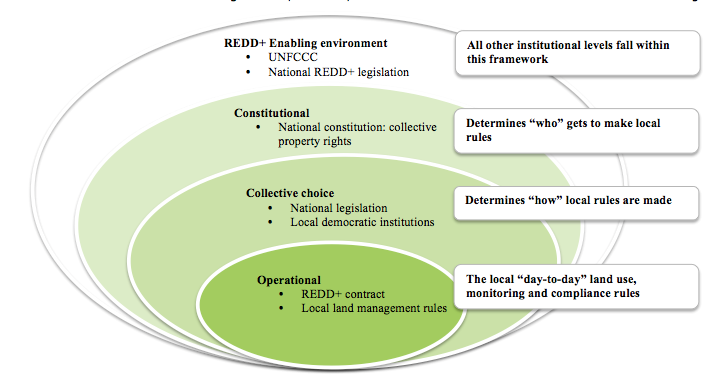

We analyzed the results of our study in terms of three levels of institutions, incorporating analytical elements from Bray (2013): those institutions that determine “who” gets to make the rules (constitutional level), those institutions that determine “how” rules are made (collective-choice level), and those institutions governing day-to-day activities (operational level).

Our results (Figure 1) indicate that those determining who makes certain rules over resources use in line with Ostrom’s first principle worked quite well (Principle 1, in blue). These rules have been established at the national level through legislation on property and collective rights. For example, communities in Ecuador are required to draw up a formal list of community members and their respective rights in order to be able to get their land titled, something we observed in all the communities we studied.

For determining how different rules were made, there were effective mechanisms in place to include residents in the decision to join the program – 70% reported that they participated in the decision to join the program. However, less than a quarter of the participants reported that they took part in making the decision about how to spend the money in the investment plan (Principle 2, in orange). We also found specific challenges with the day-to-day operational institutions that arise from participation in national state–community conservation programs. According to our study, these challenges are located within monitoring, sanctions, and conflict resolution (Principles 3, 4, 5, and 6, in green), where only 21-41% of community members reported good performance.

Overall, our results show that while some of Ostrom’s principles are met to a large degree, other principles are not. For instance, while respondents were able to participate in making a decision whether or not to join Socio Bosque, they reported that they were not able to take part in the development of the communal investment plan.

Figure 1: Average agreement reported across 94 participants from four communities participating in the Programa Socio Bosque incentive conservation program in the Ecuadorian Amazon regarding 12 measures (bars) designed to assess the first six of Ostrom’s (1990) institutional design principles

Figure 1: Average agreement reported across 94 participants from four communities participating in the Programa Socio Bosque incentive conservation program in the Ecuadorian Amazon regarding 12 measures (bars) designed to assess the first six of Ostrom’s (1990) institutional design principles

Local institutions matter

We have shown that institutions involved in the management of forests and forestlands can be found at different levels. State institutions play an important role as they establish how forests and forestlands are to be managed at the local level. At the same time, communities themselves often have their own institutions, at the collective choice level and the operational level, albeit these tend to be less visible and formal than state institutions. Nevertheless, these local level institutions are of fundamental importance when it comes to the translation, implementation and enforcement of those regulations that are provided by state institutions.

Forest canopy in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Photo by Torsten Krause.

Our study concludes that public policy plays an important role in supporting communities to establish certain local institutions for REDD+. However, developing effective institutions takes time. Local institutions are based on the way local people manage their resource on a daily basis. Thus, shaping local institutions may require a more nuanced policy approach that recognizes the limits of government reach, prioritizing and supporting local institutions. This will need to be accompanied by significant initial support for capacity building as well as contextual awareness of the interplay between top-down policies and local institutional development. For example, the community that performed best overall in our investigation was the only community that had drawn up a land management plan prior to their participation in Socio Bosque. This land management plan established locally defined rules for forest management, and appears to have strengthened local institutions for more effective local participation later in Socio Bosque.

Figure 2: Multi-level institutional framework proposed for forest governance under the REDD+ mechanism. The three institutions visible at the community level where programs are implemented (green) fit within a global REDD+ setting that is supportive of local institutional development.

Supportive enabling environment as well as strong local institutions for resource management would provide a more robust platform for shifting from current land use driving deforestation to a lower-carbon-emissions land management trajectory. We argue that, at least in Ecuador, supporting locally-driven land and forest management planning will help to create a local institutional settings necessary for an effective and equitable REDD+ implementation. We conclude by presenting a framework (Figure 2) that can support policymakers and practitioners in understanding institutional interplay between national and local levels.

This blogpost is written by Wain Collen (International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics (IIIEE), Lund University; and PlanJunto, Ecuador), Torsten Krause (Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies (LUCSUS), Lund University), Luis Mundaca (IIIEE, Lund University) and Kimberly A. Nicholas (LUCSUS, Lund University).