The 21st of November is World Fisheries Day, and this year is for the second consecutive year, aquaculture has surpassed capture fisheries by volume. What does this mean for us as consumers? Moreover, what should we be concerned about regarding aquatic food systems sustainability?

The controversial debates in aquaculture

On average, each person eats around 21 kgs of aquatic food per year. This demand goes up, driven by the growing of world population, urbanization and economic development. According to “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024” (SOFIA report), about one-third of marine fisheries stock is overfished. This raises the question: Where do our aquatic food products come from when the ocean ecologies are in crisis? This is where aquaculture products started to come into the picture.

On the one hand, aquaculture holds great hope and policy aspiration to provide enough aquatic food to feed the world. The FAO has projected that, given today’s consumption rate, aquatic food supply chains will need to keep up production by 22% to meet the global demand by 2050. A significant part of this increased supply is expected to come from aquaculture.

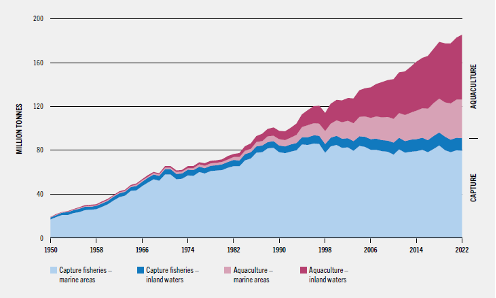

On the other hand, the fast growth of aquaculture comes with its own challenges. First, aquaculture relies on a large amount of aquaculture feed, which contributes to ocean degradation and social injustice. Fishing up the aqua-feed ingredients is often seen as harmful to local communities. For instance, the report ‘Feeding a Monster’ shows how the European aquaculture industry has exploited fish stocks from West African communities, resulting in food insecurity and livelihood loss. Additionally, examining the trends in aquaculture expansion from the 1990s to 2022 (as detailed on page 4 of the SOFA report), we see that inland aquaculture has grown from 12.1 to 59.1 million tons during this period. This significant growth raises concerns about land grabbing, disease and pollution linked to the intensification of inland aquaculture productions.

Statistic: Where to find aquaculture products?

Asia has been the main region of aquaculture production. According to SOFIA report, the leading aquaculture producers in Asia include China, India, Vietnam, Bangladesh and Indonesia. Approximately 94.6 % of employment in the aquaculture sector is in Asia. In contrast, Norway is the world’s second-largest exporter of aquatic food, just after China, largely due to its salmon industry. The growth of aquaculture production across diverse geographical regions in both the Global North and South comes with complex resource governance mechanisms and standards. However, ecological standards, such as the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC), do not cover all aquaculture products and often face criticism for excluding a diverse range of actors from participating in the rule-making of these ecological certificates.