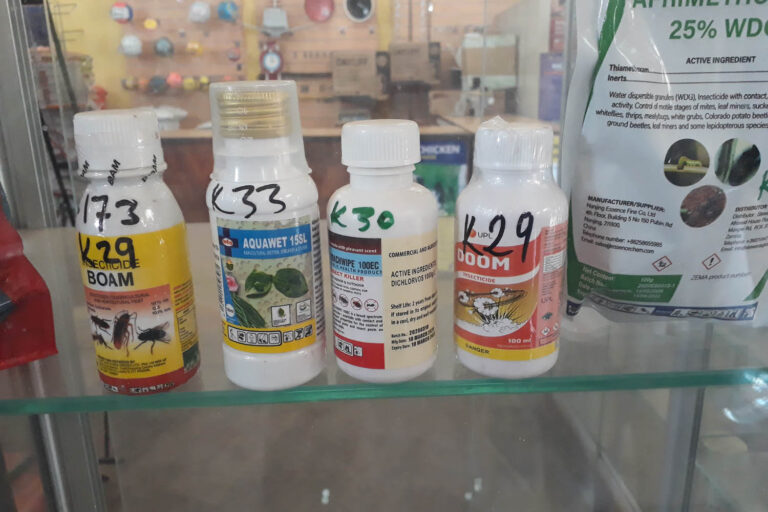

Farming in Africa is often believed to be “organic by default”, with few agrochemicals being used. Yet, recent articles (e.g., Haggblade et al., 2021, Mansfield et al., 2023) and FAO-data suggests that pesticide use is rapidly rising due to a “flood” of low-cost, generic pesticides, mostly from China and India. Some scholars call this a pesticide revolution.While pesticides promise to increase yields and reduce labour requirements, their devastating effects on human and environmental health have been a widely observed calamity of the Green Revolution.

Many pesticide problems can be minimized with better governance, e.g., by banning highly toxic ingredients, promoting integrated pest management (where pesticides are only used as a last resort), and ensuring the use of personal protective equipment. However, pesticide governance has been neglected in many African countries.

In a research project in Zambia we studied farmers’ perceptions of pesticides as well as governance challenges along the pesticide life cycle, with the aim of proposing feasible solutions for better governance. Participatory mapping techniques were methodically used to investigate the impacts of pesticides (based on focus group discussions with 159 farmers) and governance challenges (based on interviews with 87 stakeholders).

Farmers highly value pesticides and tolerate trade-offs as the necessary price to pay

The study shows that most farmers appreciate pesticides. Weighing positive against negative effects, 61.5% rated their net effects as positive or very positive – 37.5 % were undecided and 1% said that negative impacts dominate. Pesticides were seen to enable more effective control of pests before and after harvest, leading to higher yields and fewer losses, thereby reducing food insecurity. Herbicides were said to reduce the physical toil of farming and set time free for leisure, education, and off-farm business activities.

Farmers also reported negative effects; however, they appeared willing to accept them as a necessary price to pay (they may also have little choice), such as health problems (e.g., nausea, dizziness, severe accidents), which the limited use of protective equipment can aggravate Occasionally, pesticides are also misused as poison for hunting and fishing (pesticides are used to prepare baits or directly poured into rivers). Moreover, farmers noticed a loss of biodiversity, including edible insects and weeds, reducing dietary diversity.