More than two billion people suffer from hidden hunger, making it the most widespread health problem in the world. Hidden hunger is a chronic deficiency of micronutrients, often caused by poor and unvaried diets that lack sufficient minerals and vitamins.

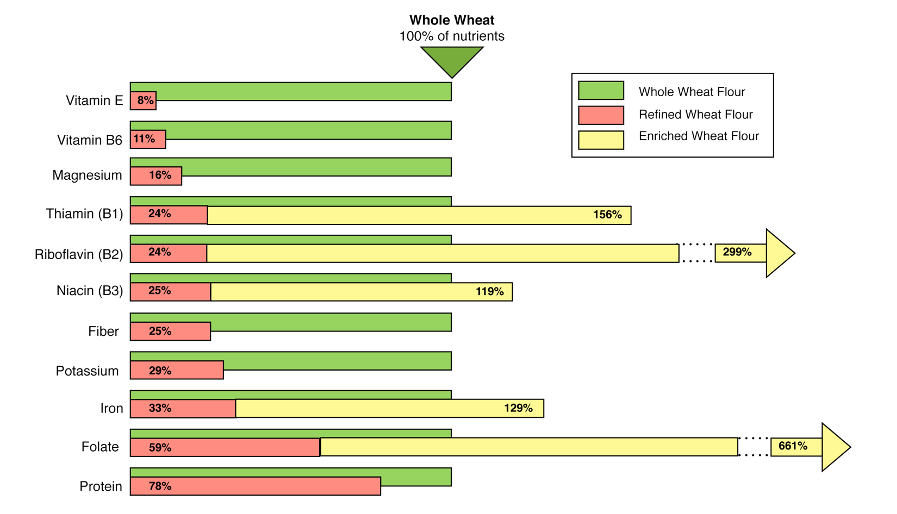

It is especially common in low-income countries where food consumption mainly consists of heavily refined wheat, maize and rice. The effects of hidden hunger are devastating not only for the individuals suffering cognitive and physical impediments but also for their societies and economies. Fighting hidden hunger requires cross-disciplinary action that ensures the micronutrients available in soils and crops can be absorbed by the human body.

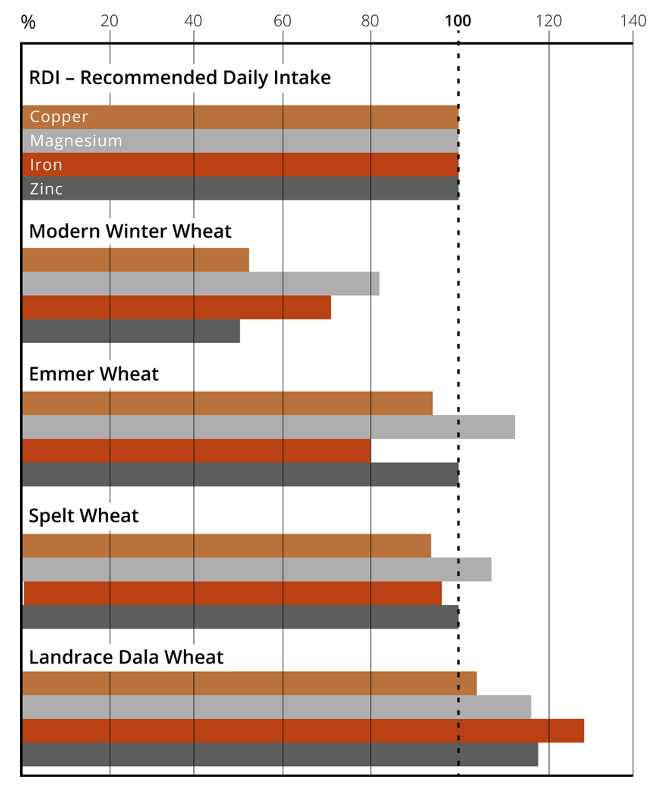

Working on the link between suppliers and consumers, food processing companies have a unique opportunity to improve nutrition through their choice of raw materials and processing methods. A SIANI Expert Group, composed of Inclusive Business Sweden, Hidden in Grains and BioInnovate Africa, has identified three actions that processing companies can take to tackle hidden hunger.

Hidden in Grains is a Swedish food company focusing on modern hydrothermal processing, a method well suited for industrial use that has been optimized in several research projects during the last decades. Our Expert Group will soon launch an online training about how food companies can implement this method.